Thin Film Processing Method: from lab to Industrialization of OPV Devices (2nd Part)

Second part: Printing techniques for industrialization

In the first part, we described the different techniques used widely in laboratories. In the second part, we go through the different techniques able to industrialize the OPV module production.

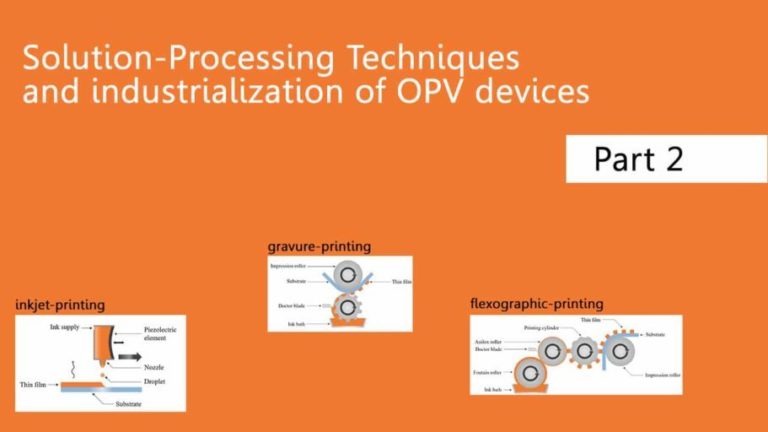

Gravure Printing

Gravure printing (also known as rotogravure printing) is used to print high-quality and high-volume printed matter and packaging. Like engraving, a gravure is a form of intaglio printing that produces fine, detailed images. The gravure printing unit consists of five parts: gravure cylinder, impression cylinder, doctor blade system, ink fountain, and dryers.

Briefly, the pattern to be printed is engraved as a discrete cavity into a rotary printing cylinder. During the printing process, the engraved cavities are filled with the ink by passing an ink bath and a flexible doctor blade is used to remove the excess ink. A chambered doctor blade system can be used for inks containing highly volatile solvent. The ink on the printing roll is then deposited when the cylinder is brought into contact with the substrate. The film is passed through a dryer to drive off the solvent or water. The thickness of the printed layer is determined by the gravure cell volume and the pick-out ratio, leading to feature lines ranging from 0.2 to several micrometers. The advantages of the gravure printing technique are its inherently simple working principle, simple printing equipment, high production speed, the stability of the process, high throughput, and high resolution. Additionally, various solvents can be used in gravure printing as the printing cylinders are made of chrome-plated copper. Disadvantages of gravure printing are the high cost of cylinders, high requirements for suitable process parameters, and high-quality demands of substrates (e.g. very smooth surface). Like flexography, gravure printing predominates in the high-volume printing of packaging, wallpaper, and gift wrap. Although less common, it also works for printing magazines, greeting cards, and high-volume advertising pieces. Importantly, gravure printing has been already successfully used to produce laboratory-scale-processed OPV cells and modules 17, 18.

Flexographic printing

Flexographic printing is Roll to Roll technology. It uses several cylinders to depose a patterned OSCs layer to a substrate. This technique differs from gravure printing mainly in the fact that the transfer of the ink is performed from relief as opposed to cavities. The final pattern stands out from the printing plate which is typically made from rubber or a photopolymer. The flexo system consists of fountain rollers that continuously transfer ink to the ceramic anilox roller which has engraved cells/microcavities embedded into the exterior. This allows the collection of ink which is then transferred to the relief on the printing cylinder that performs the final transfer to the web. The ink picks out from the anilox corresponding to the negative pattern of the motif.

This technique has been used for the printing of electrically conductive structures. Typically, inks for flexographic printing have a relatively low viscosity between 50 mPas and 500 mPas. The printing pressure is usually very low (“kiss printing”), making flexography an applicable technology for printing on rough-textured and breakable surfaces.

Despite not being studied as much in OPV research compared to other deposition methods, flexographic printing has seen some success19 and is advantageous due to easier patterning and faster coating when compared to other techniques like slot-die coating.

Screen-printing

Screen-printing is a popular technique used in a whole range of different industries, so even if you’ve never heard of the term before today, it’s likely that you’ve worn or used a screen-printed product at some point without even realizing. The process is sometimes called serigraphy or silk screen printing, but all of these names refer to the same basic method.

This technique, in contrast to flexographic and gravure printing, is a method that inherently allows for the formation of a very thick wet layer and thereby also very thick dry films, which can for example be useful for printed electrodes where high conductivity is needed. The typical wet layer thicknesses are in the range of 10–500 microns. There are two types of screen printing: flat-bed screen printing and rotary screen printing. The principle of the two methods is the same. The squeegee moves relative to the screen and forces the ink paste through the opening of the mesh, which defines the desired motif. There are significant differences in the operation of the two techniques. The advantages of flat-bed screen printing. For development and laboratory work this is a clear asset. In terms of production, it is also possible to print on very large areas (on a scale of 10 square meters). Rotary screen printing differs in that the ink is contained inside the rotating cylinder with a fixed internal squeegee and the ink is less exposed to the surroundings. The mask is a lot more expensive than the flat-bed printing mask, but in terms of speed, edge definition/resolution, and achievable wet thickness, rotary screen printing is by far superior to flat-bed screen printing by at least an order of magnitude as it is a true roll-to-roll printing technique. It is the two-dimensional printing technique that allows for the largest wet thickness achievable (> 300 microns).

Because of the cost of the mask, the more delicate operation, the more difficult adjustment, and the relatively time-consuming cleaning procedures, rotary screen printing is not as well suited for laboratory work as the flat-bed technique. This technique has been shown to be effective in the functional printing of conductive layers like printed film antenna or batteries applications. Currently, the back electrodes in large-scale produced OPV modules are mainly rotary screen printed on R2R machine 20, 21.

Inkjet-printing

Inkjet-printing is well known from home and office applications. During the recent decade, inkjet technology has made large inroads into the industrial domain. Several research studies at the laboratory or industrial scale demonstrate the strong advance of digital and specifically of industrial inkjet printing.22

In fact, inkjet has become a mature technology for graphical applications. Even in functional printing like printed electronics, 3D, and bio/pharma/medical applications, there have been successful implementations of inkjet technology.

It works generating small droplets with high frequency to realize a pattern. The inkjet-printing heads are made of one or several nozzles generating droplets. In particular, there have been several successful publications using inkjet printing to manufacture OPVs where the droplets are widely generated on demand (called drop-on-demand, DOD). The most recent ink-jet printing technology used the piezoelectric crystal to form the droplets. Under an electrical field, a piezoelectric material is mechanically deformed. First, applying a negative voltage on the piezoelectric crystal allows filling the nozzle decreasing its pressure. Then, a positive voltage leads to the droplet expulsion by increasing the pressure inside the nozzle. Inkjet-printing is a fully digital printing technique. The desired pattern is obtained using software: no mask or cylinder is required. More importantly, several studies have proven the great advantage of inkjet printing as a digital technology allowing freedom of forms and designs: large area OPVs with different artistic shapes were already demonstrated23.

Considering the fact that large area formation and roll-to-roll (R2R) processing can be done by inkjet printing, it can be a good choice for preparing homogeneous and thin layers for constructing OPV modules.

In these sections were presented the most widely used technics for solution-processed thin layer (particularly for OPV). Others printing and coating techniques could be used for the deposition of OPV layers. Interested readers should consult references presented at the end of this article.

Sheet-to-sheet (S2S) versus roll-to-roll

Doctor blading, spray-coating, slot-die coating, screen-printing, flexographic printing, gravure printing, and inkjet-printing could be adapted for the manufacturing line. Two main manufacturing ways could be distinguished for large scale production: sheet-to-sheet (S2S) and roll-to-roll (R2R).

For S2S process, the substrate, flexible or rigid, is a discrete sheet. S2S is suitable for the fabrication ofOPV modules, for instance for Internet of Things (IoTs) applications (lien vers la première newsletter : à verifier).

R2R is a well-established process used for instance for the printing of newspapers. For this process, the flexible substrate is a continuous roll of material. It requires a high amount of material and allows the production of large-scale OPV modules, for instance for building integration. As a failure during the run could impact the whole production, discrete R2R could be preferred.

The following figure shows S2S (left) and R2R (right) industrial machines compatible with OPV production a a large scale.

- Cui, Y. et al. Single-Junction Organic Photovoltaic Cells with Approaching 18% Efficiency. Adv. Mater. 1908205 (2020) doi:10.1002/adma.201908205.

- Li, S. et al. Asymmetric Electron Acceptors for High-Efficiency and Low-Energy-Loss Organic

- Hu, Z., Zhang, J., Xiong, S. & Zhao, Y. Performance of polymer solar cells fabricated by dip coating process. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 99, 221–225 (2012).

- Sachse, C. et al. Transparent, dip-coated silver nanowire electrodes for small molecule organic solar cells. Org. Electron. physics, Mater. Appl. 14, 143–148 (2013).

- K. Norrman, A. Ghanbari-Siahkali, N. B. Larsen, Studies of spin-coated polymer films, Annu. Rep. Prog. Chem. Sect. C 101 (2005) 174–201.

- Frederik C. Krebs, Fabrication and processing of polymer solar cells: A review of printing and coating techniques, Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells 93 (2009) 394–412.

- Cui, Y. et al., Single-Junction Organic Photovoltaic Cells with Approaching 18% Efficiency. Adv. Mater. 1908205 (2020) doi:10.1002/adma.201908205.- Lingxian Meng er al., Organic and solution-processed tandem solar cells with 17.3% efficiency. Science 361, 1094–1098 (2018).

- Morteza Eslamian, Ultrasonic Substrate Vibration-Assisted Drop Casting (SVADC) for the Fabrication of Photovoltaic Solar Cell Arrays and Thin-Film Devices, Nanoscale Research Letters (2015) 10:462.

- Yuanbao Lin et al., Printed Nonfullerene Organic Solar Cells with the Highest Efficiency of 9.5%, Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 1701942.

- Guoqi Ji et al., 12.88% efficiency in doctor-blade coated organic solar cells through optimizing the surface morphology of a ZnO cathode buffer layer, J. Mater. Chem. A, 2019, 7, 212–220.

- L. Wengeler et al., Investigations on knife and slot die coating and processing of polymer nanoparticle films for hybrid polymer solar cells, Chemical Engineering and Processing 50 (2011) 478–482.

- Wan Jae Dong et al., Simple Bar-Coating Process for Fabrication of Flexible Top-Illuminated Polymer Solar Cells on Metallic Substrate, Adv. Mater. Technol. 2016, 1600128.

- Yuxiu Li et al., One-step synthesis of ultra-long silver nanowires of over 100 mm and their application in flexible transparent conductive films, RSC Adv., 2018, 8, 8057–8063.

- Andrea Reale Spraet al., y Coating for Poly.mer Solar Cells: An Up-to-Date Overview, Energy Technol. 2000, 00, 1 – 23.

- Yulia Galagan et al., Roll-to-Roll Slot–Die Coated Organic Photovoltaic (OPV) Modules with High Geometrical Fill Factors, Energy Technol. 2015, 3, 834 – 842.

- Jeongjoo Lee et al., Slot-Die and Roll-to-Roll Processed Single Junction Organic Photovoltaic Cells with the Highest Efficiency, Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 1901805.

- J. M. Ding, A. F. Vornbrock, C. Ting, V. Subramanian, Pattern able polymer bulk heterojunction photovoltaic cells on plastic by rotogravure printing, Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 93 (2009) 459–464.

- Christos Kapnopoulos et al., Fully gravure printed organic photovoltaic modules: A straightforward process with a high potential for large scale production, Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells 144 (2016) 724–731.

- Alem, S. et al. Flexographic printing of polycarbazole-based inverted solar cells. Org. Electron. physics, Mater. Appl. 52, 146–152 (2018).

- Frederik C. Krebs, Upscaling of polymer solar cell fabrication using full roll-to-roll processing, Nanoscale, 2010, 2, 873–886 | 873.

- Kim, J., Duraisamy, N., Lee, T.-M., Kim, I. & Choi, K.-H. Screen printed silver top electrode for efficient inverted organic solar cells. Mater. Res. Bull. 70, 412–415 (2015).

- Handbook of Industrial Inkjet Printing: A Full System Approach, First Edition. Edited by Werner Zapka – 2018 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Published 2018 by Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

- Eggenhuisen et al. High efficiency, fully inkjet printed organic solar cells with freedom of design. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 7255–7272.